JAKARTA—Indonesia's sharia economic and business ecosystem is relatively complete. The halal industry, sharia finance, zakat and waqf-based social economy, and supporting sectors such as hajj, umrah, and halal tourism are all present and growing within a broad landscape. However, behind this completeness, progress between sectors is uneven. The real sector is actually advancing more quickly, while the Islamic finance sector—which should be the backbone—is still lagging behind and has yet to show any significant leaps forward.

Indonesia is often said to have all the prerequisites to become the centre of the global Islamic economy. "The ecosystem is complete, the regulations are in place, and the market is large. However, one fundamental question continues to arise: why is Islamic finance lagging far behind, while the Islamic real sector is advancing without coordination?" said Primus Dorimulu, Chief Kadin Communication Office (KCO) in a discussion session at Kadin Sharia Economic Outlook 2026, Rabun (26/01/2026).

Indonesia, said Primus, possesses nearly perfect fundamental capital to become a global Islamic economic hub. The world's largest Muslim population, a relatively mature regulatory framework through the Financial Services Authority (OJK), Bank Indonesia (BI), the National Sharia Council of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI), and institutional support such as the National Committee for Sharia Economics and Finance (KNEKS) have provided a strong policy foundation. However, this great potential has not yet been fully realised.

The most significant progress has been seen in the halal industry, particularly in food and beverages, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and Muslim fashion. This sector has grown rapidly because it is driven directly by domestic consumption and MSMEs, rather than financial incentives. Massive halal certification, supply chain digitalisation, and connectivity with export markets have made the halal industry the main driver of Indonesia's sharia economy. In this sector, sharia is understood as a value proposition — a guarantee of quality, cleanliness, and trust — rather than merely an ideological label," explained Primus, who is also the CEO of Investortrust.

In addition to the halal industry, the social sharia economy based on zakat, infaq, sadaqah, and waqf (ZISWAF) is also showing positive dynamics. The digitisation of zakat collection, the growth of private zakat institutions, and the emerging concept of productive waqf for MSMEs, education, and health services show that social sharia is relatively more adaptive to community needs. However, this sector still stands alone and is not yet integrated with the formal financial system as a source of sustainable long-term financing.

Meanwhile, the hajj and umrah ecosystem, including travel, logistics, and halal hospitality, is developing steadily because it is based on real needs and consistent demand. This sector strengthens the overall sharia ecosystem, but again operates without strategic links to the sharia finance industry.

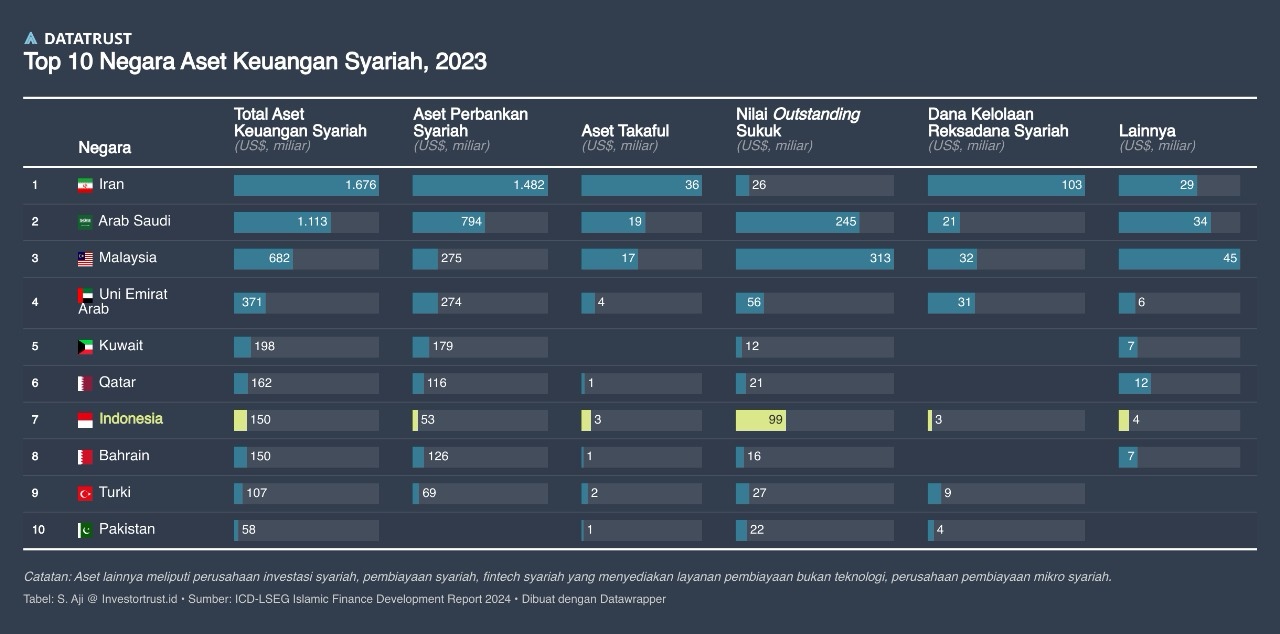

‘Ironically, amid the progress in these sectors, Islamic finance has actually lagged behind,’ he said. The national Islamic banking market share is still around 6-7 per cent of the total banking industry, while Islamic insurance is even smaller. This achievement lags far behind Malaysia, where the share of Islamic finance has exceeded 30 per cent, as well as the Gulf countries, which are major players in global Islamic finance assets.

The problem is structural. Islamic financial products, according to Primus, are often considered less competitive, with higher costs and structures similar to conventional products. Limited business scale results in low efficiency, while innovations based on true risk-sharing principles such as mudharabah and musyarakah have not developed optimally. Industry growth is also driven more by regulatory incentives than market demand, so that Islamic finance has not yet become a rational choice for the wider community.

Low Islamic financial literacy exacerbates the situation. Many Muslim consumers have yet to see the tangible economic advantages of Islamic products beyond compliance aspects. The perception that Islamic financial services are more complex and expensive remains strong, resulting in slow adoption rates. On the other hand, digital innovation and technology-based product development remain limited, including in the fintech and digital asset sectors, which often lack fatwa certainty.

This situation has given rise to a major paradox: Indonesia's sharia ecosystem has been established, but it is not connected. The halal industry, MSMEs, ZISWAF, and sharia finance are developing independently without coordination. Sharia finance does not yet function as the main enabler for the real sector, but merely as a separate sector within a fragmented ecosystem. The issue of good corporate governance (GCG) is also often highlighted as a serious weakness in a number of Islamic financial institutions.

Going forward, said Primus, the transformation of Indonesia's Islamic economy requires a paradigm shift from formal and regulatory sharia to functional and solution-oriented sharia. The integration of Islamic finance with the halal industry, MSME financing, service digitalisation, and the utilisation of productive waqf as a risk buffer are key to ensuring that the entire ecosystem moves in unison. Without strong integration and orchestration, the enormous potential of Indonesia's Islamic economy will continue to be stifled—even though its foundations have long been firmly established.

National Economy

Regional Economy

National Economy

Regional Economy